Search Results for: Joshua Boucher

Alfred Thayer Mahan: “The Influence of Sea Power Upon History” as Strategy, Grand Strategy, and Polemic

As a history of naval war Influence makes for dull reading. Rather, Mahan is interested in the more fundamental relationship between national primacy and the sea. Without commerce, territorial infrastructure, and political will, naval preponderance is unsustainable. Momentary superiority in tonnage or deployable warships often masks a deeper brittleness. As Mahan puts it when discussing the War of the Spanish Succession: “The sea power of England therefore was not merely in the great navy, with which we too commonly and exclusively associate it; France had had such a navy in 1688, and it shriveled away like a leaf in the fire.” In this respect, Mahan actually shares a great deal with later critics who highlight the importance of a dynamic economy as the ultimate source of national or imperial power. Today, U.S. strategists concerned with the vulnerability of sea lines of communication, a retreat from global commitments, or the hollowing out of the domestic industrial base, could find common cause with Mahan’s logic. Without those elements of Sea Power, pure military or naval strength is a colossus with feet of clay.

Mahan, Choke Points, and the Panama Canal

The recent blockage of the Suez Canal by the container ship Ever Given is a reminder of the importance of maritime choke points as they concern international commerce and national security. Choke points are primarily the effect of natural geography, which is one of the critical dimensions of strategy. In some cases, however, human agency, especially technology, can affect the strategic importance of natural geographic features and relationships. The shift from sail to steam, then from coal to oil-fired ships. From roads to railways. From horses to internal combustion engines. From the ground to the skies — aircraft to ballistic missiles, to drones, and hypersonic vehicles. Another human agency is the construction of canals in a way that significantly alters the geopolitical terrain.

Jimmy Carter, Commencement Address at Notre Dame University (May 1977)

In May 1977, the still comparably new-to-the-Presidency Jimmy Carter made his way to Notre Dame to give that spring’s commencement address. He used the opportunity presented to him to chart before the new graduates and the American people as a whole his plan for the foreign policy of the United States during his presidency and well beyond. The speech is best remembered for Carter’s assertion that his administration would be free of the “inordinate fear of communism” that had too long distorted American foreign policy.

Ronald Reagan, Address in Berlin (1987)

On June 12, 1987, Ronald Reagan traveled to West Berlin, to the Brandenburg Gate near the Berlin Wall, to deliver a speech commemorating the 750th anniversary of Berlin. Eastern Europe, under the sphere of influence of the Soviet Union, had closed itself off from Western Europe, often through physical means (the Berlin Wall being one of the starkest reminders of that separation). Reagan’s address spoke of a vision of Europe that was open and connected, that was no longer divided, and that was inundated with the principles of freedom. In giving his speech, Reagan attempted to push Gorbachev more fully to the side of openness. This is nowhere more clear than the famous words uttered by Reagan during his speech: “Mr. Gorbachev, tear down this wall!”

Henry Luce, The American Century (1941)

In February 1941, Henry Luce, the editor, publisher, and creator of Time and Life magazines, proclaimed to the readers of Life that America was in the war. To many of his readers, such a bold assertion probably came off as perplexing. After all, World War II, at this point ravaging Europe for about a year and half, did not involve American blood. For at least some Americans, it was unclear that the war would ever involve American blood—arguments in favor of isolation were still strong, and many Americans were unwilling to believe that the problems of Europeans could ever become their own. So how, then, could Luce make such a claim?

Reinhold Niebuhr, The Irony of American History (1952)

In writing The Irony of American History, Niebuhr provides a framework through which we can interpret, organize, and create patterns out of the facts of history. In order to do so, Niebuhr points us towards three broad categories: pathos, tragedy, and most importantly for Niebuhr, irony. The Cold War conflict between liberalism and communism, and in particular America’s role, is Niebuhr’s case study for understanding those categories of history.

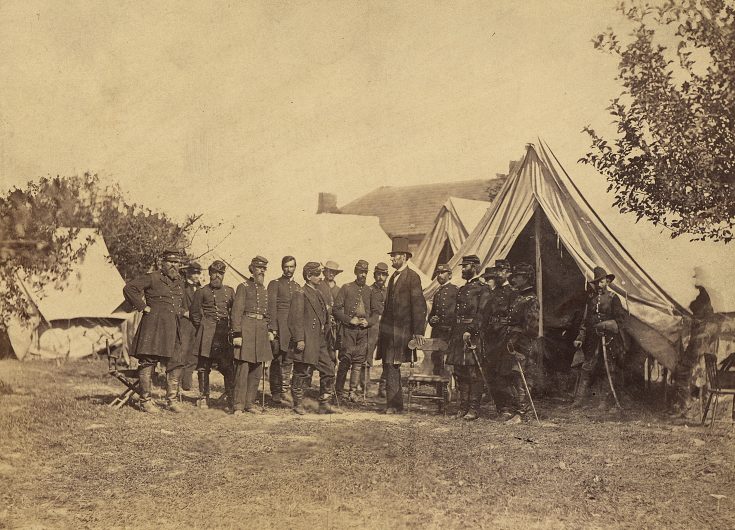

Abraham Lincoln, Reply to the Workingmen of Manchester, England (1863)

The American Civil War is imprinted upon the popular consciousness in important battlefields like Vicksburg and Antietam, in rousing speeches like the Gettysburg Address, in the Emancipation Proclamation, and in the death of Abraham Lincoln. Knowledge, or at least awareness, of each of these events goes a long way to understanding the conflict that very nearly destroyed the American Union forever. However, any understanding of the Civil War is incomplete without an awareness of the foreign policy dimension that the war possessed.

Alfred Thayer Mahan, The Interest of America in Sea Power, Present and Future (1897)

prolific writer, Mahan became one of the most famous naval and sea power prophets of the late nineteenth century. Concerned with the United States’ place in the world, Mahan wrote to influence both policymakers and common Americans. Although some of his articles and books are less resonant today, they still provide a fascinating glimpse into the state of the world of in the 1890s, shortly before the Spanish-American War, and how it was perceived by many Americans.

Instructions to Commodore Matthew Perry on the Opening to Japan (1851-1852)

“It is the President's opinion that steps should be taken at once to enable our enterprising merchants to supply the last link in that great chain which unites all nations of the world, by the early establishment of a line of steamers from California to China.” So begins a letter of instructions from Secretary of State Daniel Webster to Commodore John Aulick in June of 1851 on the subject of “opening” Japan to the outside world.